Engagement Toolbox

Creative Engagement Activities

Opening Space for Community Creativity and Learning

1. Setting the Context

Community engagement begins with creating hospitable space within which everyone can make a creative and constructive contribution. People determine quickly whether a space is safe and welcoming. The context must be set from the beginning to welcome participation, community voice and experience. An agenda and resource materials provide helpful orientation and focus, especially for those who like a “map”.

For example, setting round tables of eight in advance with paper of various colors and sizes, markers, pens and colorful post‐it notes signals that the time together will be creative and fun and that the work of the day will be shared conversation around tables vs. lecture-style expert testimony.

Try putting photos on the wall of children’s artwork to signal to parents that the children are learning and have something to teach others.

Having summary statements in poster form on the wall at the start of a meeting summarizing reports previously done honors prior work and encourages building on that foundation.

Having markers, glitter, beads, feathers, stickers with which to decorate name tags (“show us something of your sparkle, your inner spirit”) indicates that everyone brings something special and that creativity, choice and color are valued.

Reshape the physical space with participant help “in a way that enhances connections” can catalyze reflection about the impact of the shape of space on what happens within it

2. Living Questions

Having people articulate questions about which they would like to be in conversation creates an identity as a community eager to learn and invites relationship with others present. Here are several ways to quickly get to know participants quickly and focus attention on the task at hand by gathering their questions:

A. Organize table introductions around the theme of the gathering in a way which focuses attention on the topic at hand, showcases experience, encourages questions, and gathers hopes. For example, if the theme is expanding community learning, ask participants to introduce themselves to one another by sharing something that encourages learning, a current question that has drawn them to the conference, and a hope for this time together. Post their responses on the wall to create a road map for your time together. or ....

B. Take a piece of flip chart paper for each participant. Fold it in half and tear out a head space so it can be worn as a sandwich board. On the front side, invite every participant to write a “living question” they would like to be in dialogue about with others. On the back side, ask them to write something they are currently doing to pursue that question. Have the group mingle, observe each others’ questions and find 6‐8 people whose questions attract them and form a small interest group. Then have each person share the life history of their question. After they have shared these life histories, have each team decide collectively on 2‐3 questions they would like the whole group to discuss.

3. The Shape of Hope

Invite people as they are gathering: “If you would like, please draw an image that represents the shape of your hope for the future. It will help create a landscape of hope for our time together.” Participants begin drawing at their tables, spontaneously also explaining what they are doing to others as they join the table.The activity lasts about ten minutes, enough time to have many people create an image, and for latecomers to arrive. Once the conference has begun, invite anyone who wants to share their image of the shape of hope. Once a number have been shared, post the images and ask the group what they notice. This activity creates an identity as a community of hope. What people care deeply about will be honored and not judged by others.

Honoring Strengths and Values and Making Them Visible

The following activity was created for a school conference I led in Mali that included both local and expatriate staff. I went to the market to find out about local artistic practices. Mask making was prominent. I therefore used mask making as an artistic activity in which the local staff were likely to excel, to portray building strength-based relationships from the inside out .

4. Mask Making (Mali) Removing Our Masks: Sharing Our Inner Strengths

Make masks of paper with whatever materials are available. Decorate the outside of the mask –using colors, cloth, leaves, beads, etc. – in a way you think describes you as others see you. It may with wild colors and designs, to show your energy and enthusiasm; it may be neat, ordered and symmetrical, to show your planning and organization. Think of how others see you and try to represent those understandings with the materials you have.

Then on the inside of the mask, draw or write down some of the gifts or talents you have that people may not or do not know about. Also draw or write the sources of your inner strength: What gives you hope? What motivates you to do the work you do? What motivates you to learn?

When finished, share your mask with a partner, and discuss:

What environments, relationships, attitudes, times, opportunities, etc. make it possible for you to take off your mask and be yourself?

What does it mean, or what could it mean, to bring your gifts and inner strengths into more public view?

5. Buy/sell

I developed this activity years ago and have used it in many contexts where creating learning partnerships is important. I used it in a community learning day in Scotland designed to accelerate interest in retraining programs for participants displaced from closed factories.

Participants introduce themselves to someone they don’t already know by sharing why they have come and a special talent or skill they have. In mixed groups of 8, invite them to introduce themselves to one another by identifying some items on their personal buy/sell list — the ‘sell’ side comprised of talents, skills, interests, or values they bring to any group situation, and the ‘buy’ side comprised of skills or qualities they want to learn or develop this year.

Groups often discover surprising ‘matches’ between their buy/sell lists. This encourages everyone to identify themselves as joint participants in an already present learning community. A short plenary debriefing can raise awareness of the range of both skills and learning priorities within the group, and the ready availability of learning partners.

6. Speed Dating/Knowledge Mapping

It is possible to very quickly debrief the knowledge in the room around a given subject so that experience is shared and validated of all participants.

Asking the group to articulate the most important questions around which they would like to be in dialogue with others. Then post their questions and organize them into categories. Sample questions in each category are nominated on which the participants would most benefit from hearing other people’s thoughts and experience. (In working with entrepreneurs in the Ukraine, questions selected by them included, for example “What are the best ways to attract financial investors? “ “How have you established a good balance between work and the rest of your life?” “What are some tips for getting started in a new business?”) The group can select between 3‐6 questions and then organize “speed dating” teams consisting of twice that number of participants. (For instance, for three questions, teams would be in groups of 6. For six questions, teams would be in groups of 12. For 48 total participants, you would have 8 teams total if you selected 3 questions or 4 teams total if you selected 6 questions.)

If you decide on six questions, for example, and have 48 participants total, you would have 4 teams with 6 questions. Each of the four teams would need 2 copies of each of the six questions. So you would need 4x2 or 8 copies total of each of the 6 questions to distribute so everyone was curating exactly one question.

At the start of the activity. the teams would be organized in two rows of chairs facing each other holding identical copies of the questions as follows:

123456 123456 123456 123456

123456 123456 123456 123456

At the start of the activity, have each person write down the focus question they will be asking. Each person, in turn, then interviews the person opposite them for one minute about their question and records the answers on their sheet. After the first two minute round, the bottom row shifts one position to the right so the holder of question 1 is now interviewing the holder of question 2, question 2 interviewing question 3 etc....

123456 123456 123456 123456

612345 612345 612345 612345

The interviewing back and forth and then shifting positions continues for six 2 minute rounds. At the end of 12 minutes every person will have been interviewed about every question.

Once the interviews have been completed, teams are reconstituted by gathering together everyone holding question 1, everyone holding question 2, etc. ..so six teams of eight people, all of whom have heard many answers to the same question. These new teams then share, for about 15 minutes, what they learned and what was especially helpful or inspiring. Each group prepares a report summary (in words and images) to share with the whole plenary group about their question. This report can also serve as a springboard for building on the existing practice of the group in helpful ways and for sharing stories that illustrate key practices.

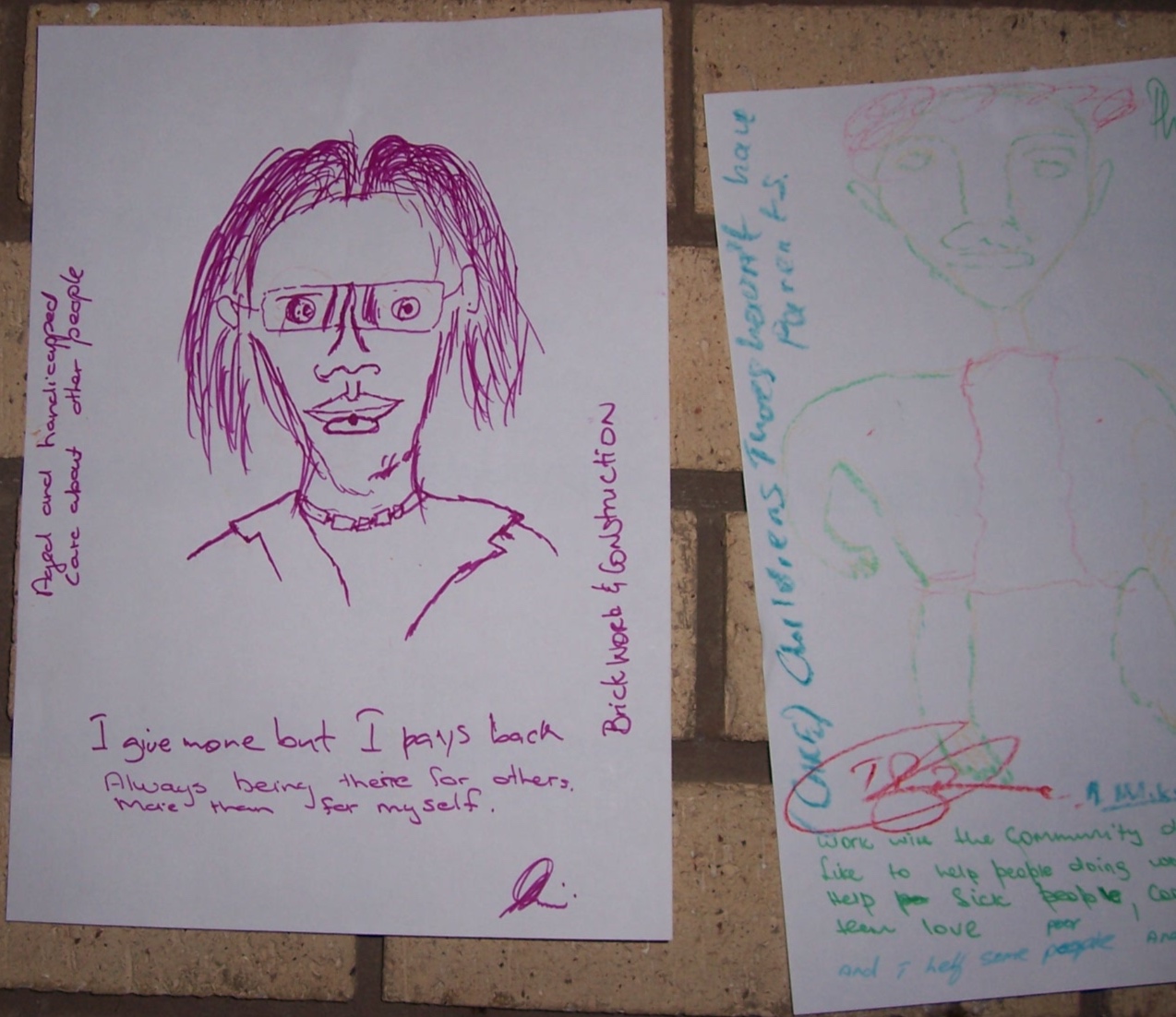

7. Portrait Activity Drawing out Strengths

This activity can be used is a variety of ways...As a way of demonstrating the power of social construction...as a way of helping participants practice seeing each other’s strengths, as a way of affirming every participant’s skills and ability to contribute to a common task like community building, as a way of demonstrating both/and thinking (building on one another’s ideas) rather than either/or thinking. Completed portraits can be mounted on the wall and become a location for adding post-it notes with additional strengths, skills, values and talents as they become visible through group activities.

Set up: Half the participants sit in inner circles of 4 chairs facing out and half sit in outside circles of four chairs facing in. Every person in the inner circle is facing a person from the outer circle. Each person in the outside circle is given a colored pencil or marker and piece of drawing paper. The people in the outside circle are the portrait artists. They will begin or help complete a portrait/visual rendering of the head and shoulders of the person facing them in the inner circle, as well as documenting at least one strength they discover through interviewing them while they are drawing.

During each round of drawing a question is asked by the artist, the answer to which is added to the bottom of the portrait or included somehow in the visual rendering. The questions can be adapted depending on the purpose of the gathering. A good general set of questions might be, for example:

What is something you know about? (head)

What is something you care about? (heart)

What's something you like to do with your hands? (hands)

What’s a direction you want to move this year (or a place you stand, that people can count on you to be or do?) (feet)

The act of illustration for each artist lasts about 60 seconds ‐depending on group size and time available. In each round, the people in the outside circle draw the person in front of them, from the shoulders up, and also interview them with that round’s question provided by the facilitator. When time is called, the paper with the portrait stays on the chair opposite its subject but the artists in the outside circle all move one position around the circle so they are now facing a new person and continuing to complete a portrait which has been started by someone else. They continue embellishing that portrait and asking the next question. This changing of positions continues until all four questions have been asked and the portraits completed and the outside circle has gone the whole round. The last person completing each portrait gets the person of whom it has been drawn to add their signature to their portrait so it is identifiable by others once posted.

Then the outside circle shifts to become the inner circle. Round 2 is repeated exactly as round one but with a new set of artists and subjects. When all have had their portrait/visual rendering done, the portraits are hung on the wall to create a gallery of all the participants (with names visible) so people can recognize each person’s creative rendering. The portraits can become places for adding more strengths the group notices about each individual as the group work continues.

8. The Heart of the Matter

This activity is a simple way of inviting many people to notice and share what is working best about a given community or organization and make it visible to others. For example, invite students on Valentine’s Day to create hearts and post them in their school about what they love best/value most about their education there.

Inspiring Possibility: The Power of Story

9. Storytelling Game

Everyone loves a good story. This activity allows stories to be shared, listened to carefully and brought into performance. The story prompt can vary. The “storytelling game” is organized as follows:

Within each group of eight, participants divide themselves into four pairs.

Each person in the pairs decides to be “a” or “b”

Facilitator asks a question of the group (e.g., tell me about an experience of community empowerment, a vivid story of something you have seen with your own eyes, when you said to yourself that people working together really can make a difference... or a story when you learned something that changed what was possible for your life ...or a story of a time of struggle that led to a place of great blessing).

“A” tells a short vivid story to their partner “B” in two minutes.

“B” tells “A” her story back, in the first person, making it “B’s” story. Two minutes.

“B” tells “A” his story in two minutes.

“A” tells “B” his story back, in the first person, making it “A’s” story. Two minutes.

A and B in each pair decide which story to share with another pair in a group of four. If “A’s” story is chosen, “B” tells it. If “B’s” story is chosen, “A” tells it.

Group one in the group of four tells its story to group two. Two minutes.

Group two tells group one its story. Two minutes.

The group of four decides which story to share with another group of four.

Group one in the group of four tells its story to group two. Two minutes.

Group two tells group one its story. Two minutes.

The group of eight then decides which story, or composite story, to enact, ‘put on its feet’.

The group of eight has 5‐7 minutes to rehearse their chosen story.

Each group acts out their scene.

When all groups have performed, they have brought to life a portrait of this group of people at this moment around the chosen topic (e.g. as an empowered community, a learning community, a community of resilience.) Sharing and enacting powerful stories invited people to see and move into a bigger story. It offers an experience of transcendence, a ritual act in which people feel honored and see the power of their lives magnified.

10. Students creating textbooks from which others learn

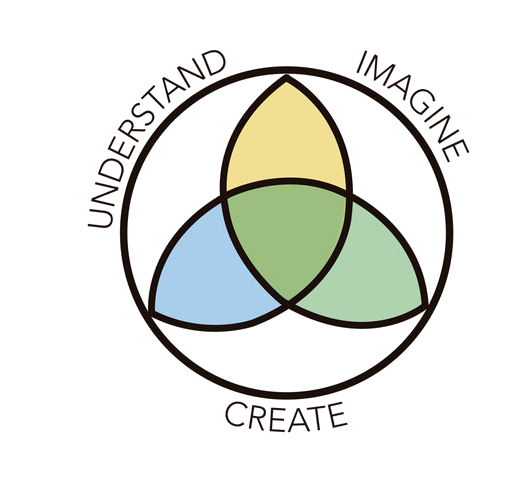

For five years, Imagine Chicago was the external partner for the Urban Imagination Network which worked with seven schools and six museums to improve reading comprehension in the content areas of science and social studies by engaging students and parents in the creation of exhibits. As participants focused on content area topics, researched those topics, and developed exhibits, they increased vocabulary, knowledge and skills. The exhibits became centers for increased school and community learning. Here is one application of Understand-Imagine-Create in a school context.

At Suder School, children worked with the Chicago Botanic Garden to create a garden in their school courtyard. Kindergartners went into the garden, and found a plant each color they needed to learn. Their teacher took a photo of the plant and student told a color story about it...”Corn is yellow. I like to eat popcorn when I watch movies on TV.” That book, with the students as curators of each color was laminated and used to teach colors to the incoming class. Similarly, the special education class wrote fictional stories. Students dressed in costumes as the characters to illustrate their stories. The book joined the class library and encouraged students to read more.

Activating Imagination and Voice about the Future

11. Appreciative Inquiries into Community Futures

Problem solving as a process for inspiring and sustaining human systems change is limited. Deficit-based analysis, while powerful in diagnosis, often undermines human organizing, because it creates a sense of threat, separation, defensiveness and deference to expert hierarchies. Community innovation methods that evoke stories, and encourage groups of people to envision positive images of the future grounded in the best of the past, have much greater potential to produce deep and sustainingchange and inspire collective action.

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a tool for doing this. Incorporating all of the voices in the community or organization, AI leverages the most positive possibilities in communities and organizations. Unlike the traditional problem- based tools and models that focus on what is not working well, AI focuses on what is working well (appreciative) by engaging people in asking questions and telling stories (inquiry). Through constructive dialogue, new possibilities are then imagined and new partnerships created to bring the desired future into being.

Communities, organizations and groups globally are adopting AI methods to cultivate hope, build capacity, unleash collective appreciation and imagination, and bring about positive change. Imagine Chicago is one of the best-known examples of applying AI in community settings. IC works to understand the best of what is, imagine what can be, and create what will be. For more on AI, click here.

What follows is one example from Imagine Chicago of conducting an An Appreciative Inquiry for Imagining Community Futures...

What stands out for you as a time you felt you were involved in a really “good” community team effort-- something significant, empowering, and effective—which gave everyone involved a way to contribute their talent and make a difference?

How and why did you get involved?

Who else was involved?

How did you work together?

What made it a powerful experience?

What were some challenges you had to deal with and did you deal with those challenges?

What did you accomplish and how did it feel?

What was especially meaningful to you about the process and result?

What did you learn about how positive community change happens?

Best qualities and skills

Yourself. Without being too humble, what is it that you value most about yourself as an active community builder? What are your best qualities, skills, values, etc.?

Others Why does working together make sense? What are the benefits and outcomes of forming strong community partnerships across generations?

Core “life-giving” factors

As you think about what it takes to build great partnerships, (especially across cultures or generations), what is the “life-giving” factor in such partnerships (without this, good community partnerships would not be possible)?

Dreams for the Future –

What three dreams do you have for the future of your community/your country?

Design: What do you think are some of the essential conditions to enable your community/your country as a whole to prosper?

Destiny: What do you consider important next steps that should be taken

+ To get more people involved in making a positive difference?

+ To help develop more productive, inspiring community partnerships?

+ To improve communication?

+ What support do you most need to plant your highest dream for the future? Who

do you most want/need as your dream team/ dreamkeepers?

Key Stages of Appreciative Inquiry

1. Setting Affirmative Topics:

What affirmative topics do you feel would be good orientation points for an appreciative inquiry based community assessment that builds community capacity and engagement?

Creating Open-Ended Constructive Questions:

Create a question you could ask anyone that would create a positive relationship with that person and get a constructive thoughtful response:

Provocative Propositions:

Create a concise provocative proposition around one of your affirmative topic choices that inspires people to be more curious about it and want to think it through in their own experience:

Moving from Inquiry into Action:

What are some ways that your inquiry could provoke action?What might be a tangible result from this inquiry?

Communities move in the direction of what they ask about. An affirmative topic serves as an orientation point for values and practices to strengthen in the community. Example: clear communication, youth as resources

Good Appreciative Inquiry questions are positive, expansive; they elicit deeply held values, passions, the best of what is. Ex. What do you especially value about this community? What’s your favorite place to go and why?

A provocative proposition invites and inspires you to think more deeply about a topic. Ex. Honest communication opens possibilities.

12. Crystal Ball - 15 minutes

Organize small brainstorming/design teams around their visions of a future worthy of their investment. Ask them to imagine themselves in the future at a certain time after the unparalleled success of their venture. Have each team ‘remember’ all the factors that contributed to its being such an unqualified success — to describe and explain in detail what had happened in the organizing on behalf of the desired dream that accounted for high participation and community involvement. Ask them to produce an extensive list of ‘what worked’. Place the lists so they can be viewed by everyone. Use these as the starting point for planning next steps.

13. Seeing with New Eyes: Images of Possibility

Change is often set in motion by becoming conscious of how we see. This activity raises consciousness about that.

In Wollongong, Australia, working with street kids, I divided kids into three teams to see the possibilities for change through their eyes . The first team was given digital cameras to photograph “in‐breaking possibilities”. (One photo they took was of a Cindy Crawford poster...with graffiti saying “we are more than our model bodies”.) The second team was asked to “photograph change makers”. The third was asked to design questions to get people thinking differently about the potential of youth and videotape interviews with people on the street using those questions (for example, “What is an important contribution kids are making to this community? What is the best thing you’ve done for/with young people this year?”) After a half hour, all photos and interviews were uploaded and shown by computer on a large screen as a meditation of how change happens. Discussion followed about constructive ways of seeing and the power of how we see and what questions we ask to produce change in a desired direction.

14. Futures Triangle

We can create only what we can imagine. To regenerate communities, communities need to reflect on and articulate images of what they want and are willing to work for. Imagining the future in concrete terms places us into a realm of freedom and possibility. To live in hope is a choice not a feeling. It can be transforming to express hopes publicly, to invite one another to do so, to create space for greater possibility, so hope gains greater authority in our public life and we can move together toward that inspired and meaningful place.

A prominent futurist in Australia named Sohail Inayatullah (www.metafuture.org) has conceptualized a way of thinking about the future which places the domain of motivation and calling as an important and orienting source of energy. It is a simple conceptual framework many find very helpful called the Futures Triangle: Think of a triangle with the three points marked PULL PUSH WEIGHT.

Sohail distinguishes three dimensions in mapping the future, thought of as angles in a triangle labeled push, pull and weight. Certain things push us into the future (shifts in technology, demographic changes, unanticipated disasters like the tsunami or Hurricane Katrina, the local river running dry). Weights of current arrangements offset this momentum for change (political structures with misaligned terms, highways in which billions of dollars have been invested to support cars, cultural patterns and mindsets that expect life to be lived a certain way, already printed business cards that keep us from moving our current offices until they run out.) Strategic planning activities often focus most attention on these pushes and weights that are known. The third dimension of futures planning is comparatively neglected‐‐ attending to those things that attract and call us forward. Human beings seek transcendent purpose and meaning. We like to be inspired; we can move in the direction of our intentions. Powerful ideas and images ‐‐ an animating vision, shared purpose, spirituality, the promise of life that our children and grandchildren vividly represent to us ‐‐ pull us into the future. Vision‐ focused conversations can mobilize energy and willingness to move in a new direction because they connect to our human need for purpose, meaning, direction and inspiration. Images have power to move us in a particular direction; they orient our choices. Positive images generate positive actions.

It is powerful in any group, at any time, to refresh the sense of intention and to explore orienting motivations and intentions. For example: Think for a minute about the images of hope that have authority in your personal and professional life, what you tell your children and colleagues about what is possible. Think about the images and stories that have inspired you here over these past few days. Think about and represent a small change in your community that could make a big difference, something so compelling and important you feel you must be about helping that change happen.

Shifting Frames

15. Reframing Tool

How can we hold space for people's anger and frustration but re-direct it to a constructive end? Here’s a framework for helping people shift to naming what they do want rather than complaining about that they don’t

As people articulate dreams or hopes, place them in the + column.

Frustrations or complaints are recorded in the don’t want (‐‐) column (often accompanied by a comment from me that “anger is simply an energy that says things need to be different. I am trying to understand what that difference is so we can organize in that direction. So I am going to put what you’re frustrated about in the “don’t want” category. I’d also like to invite you to name what you DO want” (on the premise that every complaint is a frustrated dream.) As the reframing continues, other people may announce reservations or resistances to the hope being articulated. Listen to these "buts" as naming things necessary to keep in view but help the participant reframe their skepticism them as a question that moves in the direction of the desired good. For example, “the government will never fund that" becomes “Where can we find the necessary funding?" The facilitator consistently holds the space for the conversation to head somewhere constructive. Indicators of exactly what that constructive future looks like concretely can be placed in the far right hand column. Participants can then be asked to discuss in small groups shifts they see as necessary right now and what they will take to accomplish.

16. Conversations at the Edges: Tradition, Innovation, Management

Effective change requires a variety of gifts and competencies. It must build on the best of the past, hold space for an emerging better future, and effectively manage necessary transitions. It can be helpful for participants in a change process to notice the necessary interplay of past, present and future (differently stated... tradition, innovation, and the management of change) and to actively and constantly create space for each to be honored. Here is a helpful visual and commentary for facilitating this insight and conversation.

Change happens at the intersection of the past, present, and future. In a change process, it’s important not to privilege the voice of innovation over the other two voices. If you privilege the innovative voice, you risk neglecting the past as an inventory of trustworthy possibility; the past shows and builds confidence in what has worked in a meaningful way. Everyone needs to feel their perspective and contribution is valuable to the change process. If the voice of innovation is preferenced, you may encounter resistance from conservators defended the legacy they feel is being neglected. Similarly, managers of change who excel in organizing details and structures of a change process, also need to kept engaged at every stage.

You can honor each voice in the process through a series of questions that draw on those competencies and encourage constructive dialogue in the middle. For example, if the innovator is dreaming boldly, the facilitator can ground the dreaming by asking the manager, "What and how long would it take to get that vision implemented? How much would it cost? " The historian can be asked "How can this new project build on what we've already done so that investment and legacy can be carried forward?”

17. Imagination in Prison

Sometimes conversations devolve into a litany of entrenched challenges and problems as a chronicle of a community’s negative self-image and history of disinvestment. In one such case, I invited people to spend time exploring how local imagination was being “held in prison” by the weight of many perceived constraints and what would serve to free it. Here’s the activity.

Split participants into small groups, and ask them to draw their image of imagination in prison, and to name the enslaving bars and walls. Invite them to also work together to name and depict the forces genuinely powerful enough to liberate imagination, and explore what might give access to and expand these forces. Then design a community event that would give people a taste of these imagination “liberators.” (for example, a “good enough job” might be seen as a liberator. It could be “tasted” in a several hour job fair.)

18. Visual Tools

Drawing in images as well as words can capture clarity, movement, focus and dimensionality in visioning and action conversations and activate multiple intelligences and perspectives. It is a wonderful way of gathering a group story as it unfolds and capturing high energy moments in a collective process. Whenever possible I team up with graphic facilitators and teach rudimentary graphic recording skills to workshop participants so they can also experiment with multiple ways of seeing and documenting progress.

For great examples of excellent visual tools see biggerpicture.dk. The following example is from the opening visual record of a team effort between Imagine Chicago and Bigger Picture for a Start Up Picnic organized by young social entrepreneurs in the Ukraine in 2009 for the Kyiv Hub. All drawings were done by Bigger Picture.

19. Hope Rocks

A simple question and ritual can make operating from hope a daily group practice.

Take a small stone and pass it around a circle. As each participant holds it, ask them to name one event that week (for instance in their classroom or in their family or in their department) which has given them hope.

Enabling Structures

20. Activity Organizers

Clear visual organizers for capturing conversations and action plans can help sequence a flow of thoughts and provide good, consistent and self organizing documentation from an event or project. Imagine Chicago learned about the usefulness of such organizers working in partnership with DePaul University’s Center for Urban Education on the Urban Imagination Network. For many great examples of school based curriculum organizers see teacher.depaul.edu.

Imagine Chicago has organized many programs using a series of organizers that take participants through a learning and action sequence and capture their ideas, insights and decisions as they go. A good example used for strength‐based community innovation and project management is Imagine Chicago’s Citizen Leaders Community Innovation Guide in the Resources section of the Imagine Chicago website.

Here’s an example of an IC organizer for action planning from Fayetteville Forward

Dream Planting/ Action Planning Worksheet - Small Groups Pick one dream that you’d like to act on behalf of where citizen engagement can really make a difference

Summarize your vision of something of what would make Fayetteville a more vital, sustainable community that you are committed to working for: ___________________________________________________________________

1. Conduct a brainstorm that elicits many different ways of acting on behalf of this vision. List as many ideas and resources as possible. Build on each other’s ideas. Be bold, be creative, be imaginative. (20 minutes)

2.Evaluate the ideas that you think as a group are most important and possible to implement (10 minutes)

3.Develop a set of recommended actions you are prepared to take (45 minutes). Here are some questions that may help prompt your conversation.

How will this contribute to improving the quality of life for everyone? How will this contribute to the flourishing of the local economy? How can citizens contribute? What is their role?

What is needed from government or other public institutions?

What role can the university play?

What resources are needed?

What will encourage individuals and institutions to invest in this dream?

What steps are needed to be taken now and longer term to attract the energy and investment of others?

Who will provide leadership to this effort?

What strategic partners are needed?

What’s the next thing that’s needed to build on the momentum generated today?

Ask for a volunteer recorder to bring your ideas back to the full group and enlist their support

21. Uncommon Partnerships

In 1998, IMAGINE CHICAGO partnered with British Airways to design an intergenerational conference to inspire their executives and develop their coaching skills. We connected 350 British Airway executives to 400 members of the Chicago Children’s Choir for a day of music and intergenerational education at the Field Museum of Natural History. Executives brought objects from their 83 countries of origin which represented music making, community building activities, everyday life, and ways BA provides value as a transportation company. The children prepared for the day by learning repertory from all over the world to welcome the executives to their city. Young and old worked together in pairs to design questions that focused on seeing and understanding more about global connections; they discussed what makes an effective coach by focusing on the children’s best experiences of having accomplished something with someone else’s help. Together they created traveling inspiration exhibits out of the objects that had been brought. to teach schools throughout the area about culture. The cynicism of the executives was disarmed by the enthusiasm of the children. When they had to learn a South African freedom song from the children, they remembered what it was like to feel vulnerable in a learning situation. Children discovered that adults could be fun and interesting and that airlines provide an important service. Everyone left inspired and feeling connected across generations and cultures. Not surprisingly, the following year, BA sponsored the choir’s tour to England. Read more about the British Airways partnership

22. Open Space Technology (OST)

In Open Space, groups self-organize to create their own agendas and activities. Shared leadership and diversity are celebrated, as each and every person within the group has a meaningful role and responsibility.

Open Space Technology typically begins by the group sitting together in a circle. Their time together (be it three hours or one week) is divided up into discrete time periods (usually 60‐90 minutes each). Each person in the group is asked to identify the issues they most want to discuss, around a common theme. When someone proposes an idea, s/he is agreeing to host the discussion — not to answer the question or give the solution, but simply to help facilitate a conversation about that topic. The topic, its time slot, and the location for the discussion, are posted together on a large chart visible to the entire group. The number of topics per time slot varies, depending on the size of the group and time and space constraints. Each small group is asked to report on its discussion to the whole group at the end of the meeting.

Once all the topics are posted, the different members of the group move around and join discussions according to the Law of Two Feet and the Four Principles. The Law of Two Feet asks each person to use their two feet to go to the spaces where they can learn and make constructive contributions. If they feel unable to contribute or learn in a given space, they may move flexibly and freely to another one. The Four Principles, which guide Open Space Technology are:

1) Whoever comes is the right people.

2) Whatever happens is the only thing that could have.

3) Whenever it starts is the right time.

4) When it’s over, it’s over.

The system encourages dialogue, listening and questioning. It draws upon self‐motivation and mutual respect to think through ideas and generate actions. Since each person takes responsibility for the outcome of the gathering, frustration and finger‐pointing that often plague group meetings are replaced by passionate learning through personal and collective sharing. In this way, Open Space Technology complements Imagine Chicago’s belief that engaged citizens catalyze and create open spaces for civic dialogue and collective action.

Empowering Action: Aligning Idea/Energy/Action

People find energy to create the future they have imagined when there are structures that support collective action on behalf of their visions. Focusing on individual and collective preferred futures (goals worth aiming at) also helps catalyze identification of abilities, skills and actions needed to get there.

To be productive, imagination sessions need to be followed by very practical focus on "where do we go from here and how and with whom?" What applications do we have in mind? How will we live out the values and aspirations we have identified?

23. Brainstorming bursts

Open space technology provides one way for organizing issues and interests to move forward. I often begin by hosting brainstorming sessions around a community issue on which the host moving to action wants input. The host opens the session by stating what they hope to accomplish. The group as a whole then generates ideas and afterwards evaluates the most promising ones for moving forward. As appropriate, people can then claim relevant roles and responsibilities.

Brainstorming allows a group of people to develop bold new ideas or concepts. It is generally used as a first step in creative visioning and invites the equal participation of all group members in a freewheeling, energy producing, visioning process without the fear of criticism. Engaging your team in this very important step in the decision‐making process translates into a feeling of ownership and responsibility for the success of the project. And it's energizing and fun!

All you need is a flip chart or writing surface large enough to be seen by all participants, a volunteer to record the ideas, and a comfortable setting that encourages creativity.

While conducting a brainstorming activity remember these simple guidelines:

+ The bolder the idea the better. It will encourage compelling and unique ideas.

+ Suspend all criticism or evaluation of any suggestions. Encourage all ideas!

+ Quantity not quality is the key. Evaluation comes later.

+ Encourage improvements and continuation of ideas. Bolder ideas are often

inspired by building on someone else’s idea, sometimes even in a way which is the opposite of the original suggestion!

Before beginning this exercise share these DOVE guidelines with your team:

D Defer judgment

O Offbeat ideas encouraged

V Vast number of ideas sought

E Expand on other people's ideas

Here are some tips to get the most out of your brainstorm :

+ Conduct a brainstorm during the early part of action planning

+ Review the above guidelines with all participants

+ Keep sessions short ‐‐ 15 to 30 minutes.

+ Focus the brainstorm(s) on a simple action‐oriented question.

+ Encourage ALL members of the group to contribute their ideas and build on

each other’s ideas.

+ Separate the idea generating (brainstorm) process from the evaluation

process to generate as many ideas as possible.

After completing the brainstorming portion of the exercise, give the team time to review the suggestions. With the focus person who has invited the brainstorm as the lead, as a group:

+ Cull list for duplication.

+ Clarify ideas.

+ Order/group ideas.

+ Evaluate and review ideas.

+ Develop a method of narrowing the list to the best and most feasible idea(s).

+ Report on the results of your brainstorm to other interested teams and specify ways they can become involved in moving the idea/project forward ☺.

Congratulate yourselves for a job well done!

24. Dream Pair Share

Another variation on aligning vision and action

Invite individuals to draw on cards 3 phrases and images which describe their community as they most want it to be in 20 years. Ask them to write or draw only those things to which they are deeply committed personally. When they are finished, invite them to share in pairs their visions and the reasons behind them. Each pair decides on three dreams they would like to bring to the larger group.

The pairs write their choices on moveable pieces of paper and put them on a dream wall. Once the group’s images are all up, invite the group to cluster similar dreams and title the clusters. Have each person pick the cluster to which they are most drawn. Working in small groups, flesh out the dreams into actionable steps. One way is to brainstorm as many action steps as possible for 10 minutes and then spend several more minutes sorting for the ones which are highest impact and most readily accomplished. When the groups share their action plans, ask for volunteers to serve as advocates for moving each idea forward. Those who would like to work with them say so.

25. Standing in the Future: Sustaining Community Development

Here’s an activity for thinking through long term project impact...

Imagine yourself a year from now looking back at what you have created with your team and the difference it has made. As you think about what has happened...

> What key results have you accomplished that people see have made a difference? > What have you and others done to keep the vision at the heart of the project alive and engaging?

> Who has gotten involved? How has their active leadership been encouraged? What are they now able to do as a result of their involvement?

> What new structures for ongoing involvement now exist (or what old structures have been strengthened) as a result of your project (e.g. new youth club, school‐ church partnership, community newsletter, neighborhood garden, etc.)

> What else have you done to sustain your project’s impact?

> What activities can/will you do with your own team now to set in motion planning for the long‐term?

1) At our next meeting, I/we will...

2) On an ongoing basis, I/we will...

> Now add to the Resource Bank for Sustaining Impact

Some key elements of sustaining a community development:

Keeping the vision alive as a shared vision (having whole team feel ownership in the result)

Mobilizing energy and commitment: things find a way to happen. People’s commitment sustains the project. Sharing responsibility and leadership.

Focus: action plans, calendars, organizing grids to keep vision alive and keep people focused on the next steps

Seeing results that matter

Clear communication: being able to articulate and summarize your story

Connections/Relationships: to organizations, to others doing similar things, to outside resources

Constant Learning: wanting to improve.

Documenting and evaluating the project. Learning from the project experience. Seeking tips, facts, relationships that will keep the project thriving and growing

Other? (add your own ideas...)

Harvesting Learning

Learning is much more likely to create changes in behavior if it is brought to consciousness and new commitments and practices are publicly claimed and affirmed. Here are multiple activities for doing this.

26. Learning Accelerator

Create a circle and practice passing a clap around the circle from one person to the next. Try changing directions too. Once the group has established a rhythm, have participants name things they have learned together and pass their learnings around the circle as a clap wave in both directions to show how someone’s learning can accelerate learning for others.

27. A Learning Dance

Organize participants in a circle and ask for volunteers to share something they learned this week or this month. Have them suggest a motion that captures that learning (like moving your legs in a circular motion as proxy for learning to ride a bicycle.) Have everyone in the group imitate the motion. Then ask for a second volunteer and repeat the process with them. This time add the two motions together. Do this 6‐8 times until there is a long sequence of community learning motions. Set the dance to music or rhythm and perform it as a community learning celebration dance.

28. Stepping Stones: A Project Life Line Reflection

Individual Reflection ( 15 minutes)

Identify stepping stones for your project ‐‐ important markers that come to mind when you reflect on the course your project has taken from beginning until now. Stepping stones are significant points of movement that have brought you to where you are today. They represent a continuity of development despite shifts and setbacks.

1. Reflect on the flow of choices and events, directions and detours your project has taken. These may be different stages in its development. They may include significant people who have influenced the project’s direction, events that marked a change in direction, ideas or insights that gave you a new understanding of what was needed or how to accomplish it. Think back to when you first had the idea that you are now working on or the point where others first joined together with you to act on it. Think of important things you learned or contacts you made.

Now take a few minutes to jot down six or seven major stepping stones that have brought you to where you are now in your project. Put those events onto your project’s “life‐line” (a timeline with space to annotate important markers)

2. Now take a few more minutes to look forward. What are major steppingstones you know are still on the horizon in order to fully implement your project? If you had to set a “graduation date”, a time you expect that your project will be visible to others in the community, when would that be? Mark this date on your project’s lifeline and draw a picture of what you hope will be visible.

In Small Groups of 3-4 : (30 minutes)

Share your stepping stones with each other one at a time.

After everyone has shared their steppingstones, talk about what you noticed when you did your steppingstones and listened to others.

As you look forward to the future, what structures, encouragement do you feel will be necessary/helpful to keep your project moving forward?

Have someone take notes on differences, similarities, surprises, lessons learned.

Large group conversation: (30 minutes)

Talk about reflections from small groups.

Each team presents their lifelines briefly and posts on a common chart. (2 min each)

Create group impact charts (15 minutes)

Write on to post-it notes how you think your project is making a difference in each of the following categories. Write as many notes in each category as you would like.

How I am different

How the community is different

How I would like to help sustain my project’s progress and build ongoing

community connections

Create a group chart to gather reflections and impacts in each category.29. Closing Circle

I always end any event with a closing circle, a space of shared hope and acknowledgement, for naming what had been most useful, and how people want to take forward what they have learned.

Questions are typically: What was a highlight for you? What is one way you will use something you have learned here? What next step do you plan to take?